|

|

|

Edwin

Booth

(1833-1893)

|

|

|

|

| "his

impersonation of Hamlet was vital with

all the old fire, and beautiful with

new beauties of elaboration. Surely

the stage, at least in our time, has

never offered a more impressive and

affecting combination than Mr. Booth’s

Hamlet of princely dignity,

intellectual stateliness, glowing

imagination, fine sensitiveness to all

that is most sacred in human life and

all that is most thrilling and sublime

in the weird atmosphere of ‘supernatural

solicitings,’ which enwraps the

highest mood of the man’s

genius!"

William Winter |

|

|

| Booth,

Edwin [Thomas] (1833-1893)

American actor/manager and second son

of the elder Junius

Brutus Booth. He

was born on November 13th on the Booth

family farm in Belair, Maryland, and

is best remembered as one of the

greatest performers of Shakespeare’s

Hamlet. He was a member of a famous

family of actors. His father Junius

Brutus (1796-1852) achieved popularity

second only to that of Edwin

Forrest.

His two brothers were Junius Brutus,

Jr. (1821-1883) and John Wilkes

(1839-1865), the assassin of President

Abraham Lincoln. Edwin however out

shown all of them and is universally

recognized as the greatest tragedian

of the 19th century American stage.

At the age of 13 he

accompanied and chaperoned his

eccentric father on his acting tours

where he endeavored to keep him sane

and sober, at the same time absorbing

the rudiments of acting. On September

10, 1849 at the age of 16, he made his

acting debut at the Boston Museum

playing Tressel to his father’s

Richard in Colley Cibber’s version of

Richard III. His performance met with

his father’s disappointment and

members of the theatrical

professional, who holding Junius

Brutus in great reverence, agreed that

his genius had not been passed onto

the son. A year later Edwin made an

unobtrusive New York appearance as

Wilford in The Iron Chest at

the National Theatre in Chatham

Street. It was not until the following

year that he received any attention

when at the last minute he filled in

for his ailing father as Richard III.

In 1852, under the management of

Junius Brutus Booth, Jr., Edwin

accompanied his father on a tour to

California. It was when his father

left to return to Maryland and died on

route later that year that he began to

establish an unassailable position for

himself on the stage. He remained on

in California playing San Francisco,

Sacramento and barnstorming through

the California mining towns. In

1854-55, he toured Australia and the

Sandwich Islands (now Hawaii). It was

on these tours that he mastered

virtually all of the roles for which

he would become famous, notably

Hamlet, Cardinal Richelieu, and Sir

Giles Overreach in A New Way to Pay

Old Debts. Those who had known him

back East were surprised when news

came that he had captivated his

audiences with his brilliant acting.

On his return to New York in 1857 he

was billed as "the hope of the

living Drama." His season not

only included Hamlet, Richelieu

and Sir Giles Overreach, but also King

Lear, Romeo and Juliet, The Lady from

Lyons and Othello (in which

he played Iago to Charles Fisher’s

Moor) as well as several now forgotten

works. From this time forward his

dramatic triumphs were warmly

acknowledged. His Hamlet, Richard III,

and Richelieu were pronounced to be

superior to the performances of Edwin

Forrest and his success as Sir Giles

Overreach surpassed his father. But

for all his praise, Booth had not yet

overcome the unruly temperament

inherited from his father. His acting

was occasionally fuddled by drink,

leading critics to say that even as

fine as his acting may be in one scene

there is no guarantee that he will not

walk feeble through the next, and let

it go by as if by default. In 1860, he

married the actress Mary

Devlin, by

whom he had his one surviving child, a

daughter, Edwina. It was the double

shock of Mary’s untimely death in

1863 and his failure to be at her side

because he was too drunk to respond to

the summons of friends that henceforth

made him abstemious.

By 1862,

when he took over management of the

Winter Garden Theatre his acting had

improved, although the critics still

complained about the unevenness of his

performances. While at the Winter Garden

he mounted many highly praised

Shakespearean productions at the house. In

all cases Booth used the true text of

Shakespeare, thus antedating by many

years a similar reform in England.

On November 25, 1864, all three

Booth brothers (Edwin as Brutus, Junius

Brutus as Cassius and John Wilkes as

Marc Antony) appeared together for the

only time in their careers in a benefit

performance of Julius

Caesar. The

performance being memorable both for its

own excellence and for the tragic

situation into which two of the

principal performers were subsequently

hurled by the crime of the third. The

following night on November 26th, Edwin

began a 100-consecutive nights

performance as Hamlet, the longest run

the play had ever had until that time.

He was thereafter identified with the

part for which his extraordinary grace

and beauty and his eloquent sensibility

peculiarly suited him. Less than a month

later, when John Wilkes assassinated

President Lincoln, Edwin went into

retirement and did not appear on the

stage for nearly a year. The incident

was a blow from which Edwin’s spirit

never recovered. When on January 1866,

he reappeared as Hamlet at the Winter

Garden Theatre, the audience showed by

unstinted applause their conviction that

the glory of the one brother would never

be imperiled by the infamy of the other.

When the

Winter Garden Theatre was destroyed by

fire, Booth built his own theatre (Booth's

Theatre) on the southwest corner

of Sixth Avenue and 23rd Street, opening

it on February 3, 1896, with Romeo

and Juliet. That same year, his

Juliet, Mary McVicker became his second

wife. But her nervous instability made

for an unhappy marriage. With an

excellent stock company, Booth mounted

many successful Shakespearean and other

productions including Romeo and

Juliet, The Winter’s Tale, Julius

Caesar, Macbeth, and Much Ado

About Nothing. Unfortunately, with

the playhouse sitting on the edge of the

main theatre district combined with a

lack of business acumen and a generous

and confiding nature, his ventures were

unsuccessful and he lost the theatre in

1873. With the raising of the grand

dramatic structure in 1874, Booth lost

everything and at the age of 40,

declared bankruptcy.

Ultimately

by hard work he recovered from his loses

and again accumulated wealth. He toured

the country and from 1880 to 1882

performed successfully in England and

Germany. Booth first acted in London in

1861 and when he returned in 1880, his

appearances at the Princess Theatre were

near failures until Henry

Irving, star

and manager of the much superior Lyceum

Theatre, invited him to costar at the

theatre in what proved to be a memorable

engagement with the two actors

alternating Othello and Iago. In 1882,

Booth played England again and the next

year toured Germany where the acclaim

given his Hamlet, Iago and King Lear

(considered, after Hamlet, his finest

roles) made the German engagement the

peak of his career.

On his

return from Europe, his financial

affairs improved permanently when, in

1886, he formed partnerships with the

Helena Modjeska, Madame Ristori and

Tommaso Salvini. But it was several

extensive US tour in association with

business and acting partner Lawrence

Barrett from 1886-91 that is the most

noteworthy. In 1888, his generous nature

was exemplified when he converted his

spacious residence on Grammercy Park

into a Club (The

Players) for actors and

eminent men in other professions. He

retained an apartment there until his

death. His farewell stage

performance was as Hamlet in 1891 at the

Academy of Music in Brooklyn. He died on

June 7, 1893. A statue of Edwin Booth

was erected in 1918 in Grammercy Park

opposite the Players, making Booth one

of the rare actors so honored. Booth

stood about five feet six inches tall.

His black hair, dark complexion, brown

eyes, and sad mouth gave him a slightly

Latin or Semitic appearance. Among the

roles that he played over the course of

his career were Macbeth, King

Lear, Othello,

Iago, Shylock, Wolsey, Richard II,

Richard III, Benedick, Petruccio,

Richelieu, Sir Giles Overreach, Brutus

(Payne’s), Bertuccio (in Tom Tyler’s

The Fool’s Revenge), Ruy Blas,

Don Cesar de Bazan and his most famous

part, Hamlet.

Booth’s

personal life was as plagued by tragedy

as any of the characters he portrayed.

His father and several other close

family members died insane; both his

wives died young; his brother’s murder

of Lincoln gave him his blackest moment;

and financial and drinking problems

often beset him. Quite possibly it was

the daunting distractions of his

personal life that determined his

conservative approach to acting. His

acting style was quieter than his father’s

has been and became increasingly more

sensitive and subdued. Unlike Edwin

Forrest, he never sought to promote

native plays; unlike Barrett, he never

risked reviving obscure or neglected

masterpieces. From early on he

recognized that he had only small

ability in comic or in basically

romantic plays. Tragedy was his forte,

and he remained content with his

reasonably large but relatively safe

repertory. |

|

|

|

(click

on photo to enlarge) |

|

|

|

|

| Birthplace

in Belair, MD |

Booth's

father

Junius Brutus Booth |

father

& son, age 13 |

|

|

|

| Junius

Brutus Booth |

Junius

Brutus Booth, Jr. |

John

Wilkes Booth |

|

|

|

| Painting,

age 19 |

1852,

age 19 |

1854,

age 21 |

|

|

|

| After

his return from CA, 1857, age 24 |

Mary

Devlin |

1860,

at the time of his marriage to Mary

Devlin |

|

|

|

| Mary

Devlin Booth & daughter Edwin,

London 1862 |

|

Edwin

& daughter Edwina, 1864 |

|

|

|

| 1864,

age 32 |

|

|

|

| with

daughter Edwina |

sketch |

Portrait |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

as

Hamlet |

|

|

|

| Winter

Garden Theatre |

Julius

Caesar Playbill |

The

three brothers in

Julius Caesar |

|

|

|

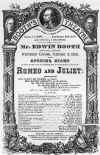

| Booth

Theatre |

First

Playbill at

Booth's Theater |

Witham's

set design for Hamlet at Booth

Theatre |

|

|

|

| Articles

belonging to Edwin Booth |

Booth's

dressing room

Broadway Theatre

December 1889 |

Articles

belonging to Edwin Booth |

|

|

|

|

| as

Benedick |

|

as

Hamlet in 1887,

age 54 |

|

|

|

| as

Richard III |

as

Betuccio in

The Fool's Revenge |

as

King Lear |

|

|

|

|

as

Iago |

|

|

|

|

Sargent

portrait that hangs in The Players |

|

|

|

|

|

bust

as Brutus |

sketch

of assasination attempt |

bust

as Hamlet |

|

|

|

|

as

Richelieu |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| with

granddaughter |

in

his last days |

Booth

family tombstone |

|

|

|

Unveiling

of Booth's statue in

Grammercy Park |

inside

The Players Club |

Booth's

Statue in Grammercy Park |

|

|

|

|

|

(click on the gramophone

to hear Edwin Booth's recording of his

Othello)

Othello, Act I Scene 3

Most potent, grave, and

reverend signiors,

My very noble and approved good masters,

That I have ta'en away

this old man's daughter,

It is most true; true, I have married

her:

The very head and front of my offending

Hath this extent, no more. Rude am I in

my speech,

And little bless'd with the soft phrase

of peace:

For since these arms of mine had seven

years' pith,

Till now some nine moons wasted, they

have used

Their dearest action in the tented

field,

And little of this great world can I

speak,

More than pertains to feats of broil and

battle,

And therefore little shall I grace my

cause

In speaking for myself. Yet, by your

gracious patience,

I will a round unvarnish'd tale deliver

Of my whole course of love; what drugs,

what charms,

What conjuration and what mighty magic,

For such proceeding I am charged

withal,

I won his daughter. |

|

|

|

Joseph

Haworth & Edwin Booth

|

|

Edwin

Booth played Ellsler’s

theatre several times while Joe was working there.

Joe played Laertes in Booth’s Hamlet, Cassio in

Othello, and Edward IV in Richard III.

Ellsler was sharing productions with a theatre in

Pennsylvania at this time, so Joe and Edwin Booth

toured there together and became very close

friends.

Here are three

quotes from Joseph Haworth regarding

Edwin Booth:

"I had the honor

while still in my teens of supporting

our own idol and ideal actor, Edwin

Booth. I appeared in Hamlet,

Othello, Lear and Macbeth;

also in The Fool’s Revenge and

Richelieu. My first meeting with Mr.

Booth was while playing in John

Ellsler’s stock company at the Euclid

Avenue Opera House, Cleveland. To this

latter gentleman I am indebted for my

earliest years upon the stage and

probably my most pleasant results since

achieved.

"I had read of the

tragedy that cast a mantle of blackness

around our hero of the stage for a brief

period and left the stamp of everlasting

sorrow on his pale, intellectual brow

and in his luminous eyes, and that

served to create in our own imaginations

the ideal Hamlet, Iago, and Lear.

Naturally, when the announcement came

that the great artist was coming to play

at ‘our theater,’ I was much exercised

and grew frightfully nervous---having

been cast (for the first time) for

Laertes, Cassio, and Edward IV in

Richard III. Henry Flohr was Mr.

Booth’s stage director, and he came two

weeks in advance to lighten the labor of

the master by drilling supernumeraries

and giving the principals the stage

business of the various plays. What

troubled me was my anxiety to please in

the foiling bout in the last act of

Hamlet. I played the part with all

the nervous force I possessed, and

perhaps a little more; and---reaching

the final scene---I met on the boards

for the first time Edwin Booth, as

Hamlet, face to face. There was

something indescribable in that look; I

was unnerved, and looked my

discomfiture. My heart seemed to come up

into my throat, but, as some one has

said, I had "presence of mind to swallow

it." Trembling visibly (Mr. Booth noted

it), I tried to fence, but was too

frightened. Mr. Booth smiled and said,

"You’re all right my boy; begin. The

encouragement of those sotto voce

arguments was all I needed. I fought

well, and when the final curtain was

lowered Mr. Booth came, assisted me to

rise, and said: "Young man, that is the

first time the fight has gone perfectly

the opening night." "I thank you," I

choked in earnest, went to my room,

disrobed, and shot home to my dear old

mother to tell what Mr. Booth had said."

"Having in play

accompanied him to Venice, Padua,

Denmark, France, Verona, and England, at

the conclusion of one performance he

asked me with all his princely grace, to

accompany him in person to supper.

Hastily dressing I knocked on the door

of Mr. Booth’s dressing room. Thrilling

with varied emotions I announced

modestly that I was ready to go.

" ‘Go?’ he asked.

‘Here’---and he produced a bag of

peanuts and a pitcher of beer. This was

not the ‘Feast of Lucullus,’ but by way

of dessert he informed me, after a feast

of reason and flow of bowl, I mean soul,

that I was destined to become a genius.

"Elated beyond

expression I bade him goodnight and

hurried home, only to meet another

disappointment, for on asking my mother

the real meaning of genius she, with her

usual frankness, quaintly replied: "It’s

a very bad thing to have around the

house."

"(Mr. Booth) was

simplicity itself off the stage; quiet

and retiring; deeply, not showily,

intellectual; and at our club---The

Players,’ which he gave us in his later

years---he loved to conjure up memories

of his youth and early struggles. Once,

when I complained that the classic drama

has gone to sleep (and as my aim had

always been to excel in that line of

endeavor I felt discouraged), he

replied:

‘Look at the years

I had accounted lost while in

California. I could act then; I had all

the enthusiasm of youth---rosy hopes,

great ambitions, etc; yet I could not

convince the people I was a good actor.

But, you see, it was a foundation I was

laying upon which to build my future

temple. I am now old and they are paying

five and ten dollars a seat, and I

cannot act at all. Yet it sometimes

occurs to me that art should be

encouraged more heartily in its budding

infancy.’"

"Booth’s Iago was

subtle and thoroughly Venetian in tone;

his Richelieu the most finished I had

ever seen; his Lear a masterpiece;

The Fool’s Revenge perhaps his

greatest performance. Brutus, in The

Fall of Tarquin, was also a superb

performance when he was minded to enact

it." |

|

|

|

|

Top

of page |

|

|

|

|